Pistachio Towers

SIte of huge city planning controversy

Despite acres of high-rise housing on the outskirts of the capital, planning consent rules in Budapest limit buildings to below the height of the Parliament or the Basilica. Each is 96 metres (315 feet) tall but both were well exceeded by the construction of the MOL Campus tower during the Covid years. The rumour is that control was eased for one day. Time enough to grant permission for the 143 metre (469 feet) high headquarters of the national fuel supplier to be built. Currently, Hungary’s tallest building. When compared with the Gherkin or Cheesegrater, this is not of a pleasant, spectacular or original style. Some locals were amused, when its evening lighting revealed male office workers standing in front of urinals on the first floor, prompting lurid comments about the inspiration behind the design of the tower. Budapest’s first ‘skyscraper’ was not to the liking of many local people. Situated just to the south of the city centre, at least it hasn’t spoilt the beauty of nineteenth century Pest and seems to have been reluctantly accepted by most.

More controversial were the plans for a ‘mini-Dubai’ or officially named, Grand Budapest development; just to the north of the city park. Last year the government attempted to sell a huge piece of derelict land, alongside the freight yards of Rákosrendező station, to the Eagles Hill Group from the UAE. The deal for 50.9 billion forints would have seen the construction of Europe’s tallest building, a shopping centre, housing and other facilities. The main tower was planned to be three times the height of the Shard at London Bridge, currently the continent’s loftiest structure. There is little doubt that the target market for the housing and other services would be the global elite. The plans didn’t include any provision which would address Budapest’s housing needs and failed to become popular.

The Rákosrendező site has been neglected for 34 years

Few would disagree that something needs to be done with the 320 acres of dead space surrounding the tangle of railway lines a mile or so, to the north of the Nyugati terminal. Rákosrendező was the largest goods station in Hungary and significant in connecting the country with other member states of the Austro-Hungarian Empire during the dualist period (1867-1918). Following the Empire’s defeat in the First World War, the Trianon peace settlement of 1920 saw Hungary lose two thirds of its land and more than half of its population to neighbouring countries. As a result, Rákosrendező saw its role diminish until communism took hold after World War II. During the years of the Comecom agreement, trade between Hungary and other Warsaw Pact countries gave the station a new lease of life.

When the Soviet period ended around 1990, the station went in to decline again. In just thirty-four years a huge wooded area has grown up around the lines and abandoned buildings. Official and unofficial fly tipping has turned parts of the area into a huge rubbish dump. The land beneath the plethora of tracks remains badly polluted. Part of the mini-Dubai deal was to pay for the land to be cleared and cleansed before new building commenced. A huge financial undertaking.

The fly in the ointment for the government turned out to be a clause in the agreements around the original ownership of the railway land. It meant that although the state was the majority owner of the site, first refusal in terms of a sale had to be granted to any minority landowners here. The Budapest municipality were also stakeholders and able to exercise their right to be offered the site before outside interests could intervene. The Mayor of Budapest subsequently exercised this right, scuppering the widely publicised deal with the UAE, with the explicit intention of not elevating Budapest into the skies or accepting a solution which only benefitted the super-rich.

At least, this is the official explanation for what happened. Rumours abound that Viktor Orban’s two- day visit to Dubai was a futile effort to rescue a deal that was fast heading south anyway, rather than west. Whatever really happened, the Budapest municipality paid the same price initially agreed with the consortium from Dubai. Grand Budapest, as the government finally designated the scheme, has bitten the dust and the cash strapped council must decide what to do with this huge site instead. Selling it on to private developers who will implement a more conservative, lower-rise solution, hopefully with affordable housing, seems the most likely outcome.

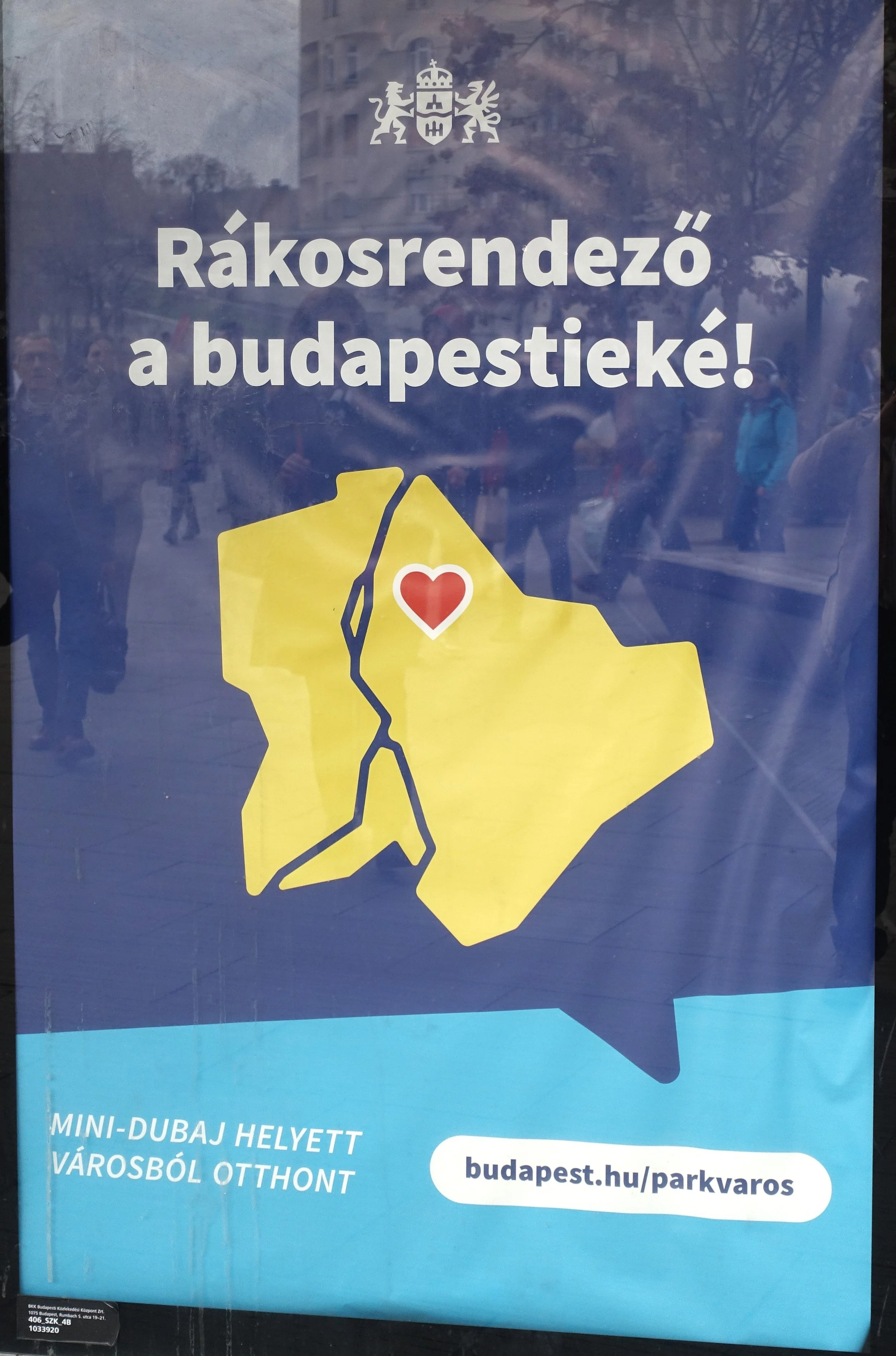

Budapest council have produced a low-key poster at transport hubs celebrating their victory. Low-key probably because of the huge challenge, financial and otherwise, of developing this area. I have previously travelled through on passenger trains heading towards the Danube Bend but never visited Rákosrendező on foot before. Amazed that this huge undeveloped space could exist in such a central location, I was curious to see what was happening on the ground, now that the initial plans have failed to materialise.

Budapest council poster proclaiming Budapest is for the people of Budapest

Looking down the tracks towards the Biodomes of the City Park.

I discovered one crossing point for public traffic near the passenger station, which is closed and dilapidated, but as the city’s oldest railway building, remains standing under a conservation order. There are a double set of level crossing gates and traffic backs up Szegedi út, with lengthy waits to make use of the short cut between districts thirteen and fourteen. During my visit, the delay was too much for some foot passengers and food delivery riders who managed to squeeze through a gap just wide enough to take their handlebars. All took a chance to hurry across the tracks watching out for trains heading into or out of Nyugati railway terminal.

Wasteland at freight yards has developed into woodland as nature takes over

I was there for at least ten minutes without a train to be seen and became tempted to follow the transgressors, when a police car arrived. A food delivery cyclist and female pedestrian were stopped by two rather angry police officers who demanded identification from the offenders and gave each a severe dressing down for crossing the tracks at the wrong time. It was too embarrassing to witness, so I explored the waste land and nearby derelict buildings instead. Only a few minutes from where the law of the land was being enacted, a man in his twenties attempted a precarious walk along the pitched roof of a broken-down building. The reputation of the area is that of a ‘drugs den’ and it can only be supposed that some kind of self-medication had precipitated this act of foolishness. And would certainly be required should he have fallen. I chose not to ask him why he was carrying out this circus act without pay and only myself for an audience. These wastelands have become a landing ground for the city’s addicts and homeless. Not a place for a carefree wander.

Abandoned buildings near the tracks

Once over the first level crossing, I noticed that passenger trains still stop here on their routes north and west and a handful of people waited in the most exposed of surroundings. Otherwise, railway workers dug holes and peered into them. To the south the biodomes at the end of the City Park were shining in the midday sun. Workers queued at the Rákosrendező Bufe, a throwback to the revival of private enterprise in the 1990s. Despite the surrounding neglect, this popular old-fashioned eatery serves a useful purpose and reminder that this remains an important junction. Although most of the freight lines left in place take you nowhere, this is still central Budapest and some kind of solution, housing or otherwise, will eventually have to be found. Major fires frequently break out in piles of old railway sleepers. Only last week a huge blaze had to be extinguished in the heaps of garbage.

Taking the number fourteen tram homewards, my thoughts turned to the latest craze sweeping through the confectionary world in Hungary. Around the same time that plans for Grand Budapest were crumbling like a stale Aero bar, Dubai chocolate has become widely available. Initially served up in expensive ‘boutiques’ in the city centre, supermarkets now offer cheaper versions of this pistachio cream delight. Sweet and nutty and nothing like an aero bar, one wonders what future this Middle Eastern import has here. Last week I saw a liquified version of Dubai chocolate on offer in the Central Market for approximately £14 per drink. Like the plans for Grand Budapest, it may be just a costly passing fad, driven by Tik Tok and other social media, and soon to be replaced by the next marketed gimmick.

What will happen at Rákosrendező remains to be seen. While the government wanted to proclaim the loftiest of Middle Eastern palaces, the council have purchased an expensive white elephant. One which will hopefully trample down the wasteland in the name of Hungarian urban development. Even if some of it hails from the EU in the first place, the failure of Grand Budapest is further evidence that Hungarians care very much about how their money is spent in their homeland

Dubai style chocolate available from Spar supermarket.