Downstream of Storm Boris

While Hungary experienced unseasonal and heavy rain this September, the Danube rising was mostly a result of Storm Boris raging in Germany, Austria and Slovakia. Melting Alpine snow each spring always brings high water levels but rarely has the river risen in the autumn to the degree experienced this year. It happened at the end of a prolonged summer heatwave when cold autumnal air from the north collided with the blanket of warmth still lying over Central Europe. It happened when Budapest was full of fine weather tourists and the leaves still on the trees. Conkers fell as the thermometer climbed to thirty-four degrees Celsius. Further signs of global warming… surely?

The Danube surges through the capital of Hungary with much gusto. Like an impatient weekend guest, it wants to tick-off all those tourist sites it helped create in the first place. Europe’s second longest river unites, divides and shapes Budapest like no other city along its course. Yet on an everyday basis it’s only as remarkable as the sky or a road. With plenty of bridges and two Metro lines connecting Buda and Pest, people can easily go about their daily business. The ‘Duna’ is just there-- a greeny, brown expanse to be crossed over or under. Sometimes it’s misty grey or gains a pink tinge at dusk but I don’t ever recall seeing a Blue Danube.

It took the recent floods to remind me that this river is more than a wavy line on the map. More than a social and geographical boundary. The recent high waters made connectedness with other places and countries feel real: that the vague area called Central Europe might actually exist. I remember a colleague claiming that she could smell salt off the river. That somehow, the fragrance of the Black Sea had drifted from the edge of Asia to the centre of Europe. An olfactory illusion but a romantic thought nonetheless. There is only light traffic now, but once the Danube was an important trading route. From Ottoman lands, Greek, Turkish and Serbian influences came to bear in multicultural neighbourhoods like the Tabán. Now it’s a riverfront area in Budapest only memorable for an ugly knot of a road traffic system, high above the flood line.

Of course, extreme weather has happened before. The flood of 1838 was so devastating for low-lying Pest that the present-day city was rebuilt several metres higher. There are markers in the Víziváros district showing how high the floods in Buda reached in 1876. More recently, 2003 saw an 848 cm rise in the water level and in 2013 an 891 cm rise, bringing fears of serious flooding. The river peaked on September twenty-first this year at 832 cm above the normal level. Hardly ‘the flood of the century’ as some local media pundits dubbed it, but still concerning to life and limb. Fortunately, the engineers of the past have done a good job with river defences.

Unexpected weather is a problem for event planners at any time of the year. On August 20th, 2006, as 1.5 million people packed the Danube shore, awaiting the annual firework show that marks the National Day, a freak summer storm descended. Three people lost their lives in the river and 300 were injured in the ensuing panic. In 2023 a similar storm was predicted by the national weather forecasting service. Fearing a repeat of 2006, the government made a late decision to cancel the firework show. There were huge dark skies that evening but hardly a drop of rain fell. The next day the head of the meteorological service was sacked by the government. Similar fears emerged this year but delaying the fireworks by an hour, meant the most expensive display ever seen in Europe, costing nearly 38 million Euros, went ahead smoothly.

Clearly, when the weather turns nasty, the Danube brings a huge, fast-flowing threat to Budapest life. The pleasure boats and kayaks have to take its currents and eddies seriously. On a particularly stormy night in May 2019, a large river boat pushed a smaller one under the bubbling surface. The Korean government have erected a monument next to Margaret Bridge, to remember their twenty-five citizens lost in this accident . Two crew members also perished alongside the tourists.

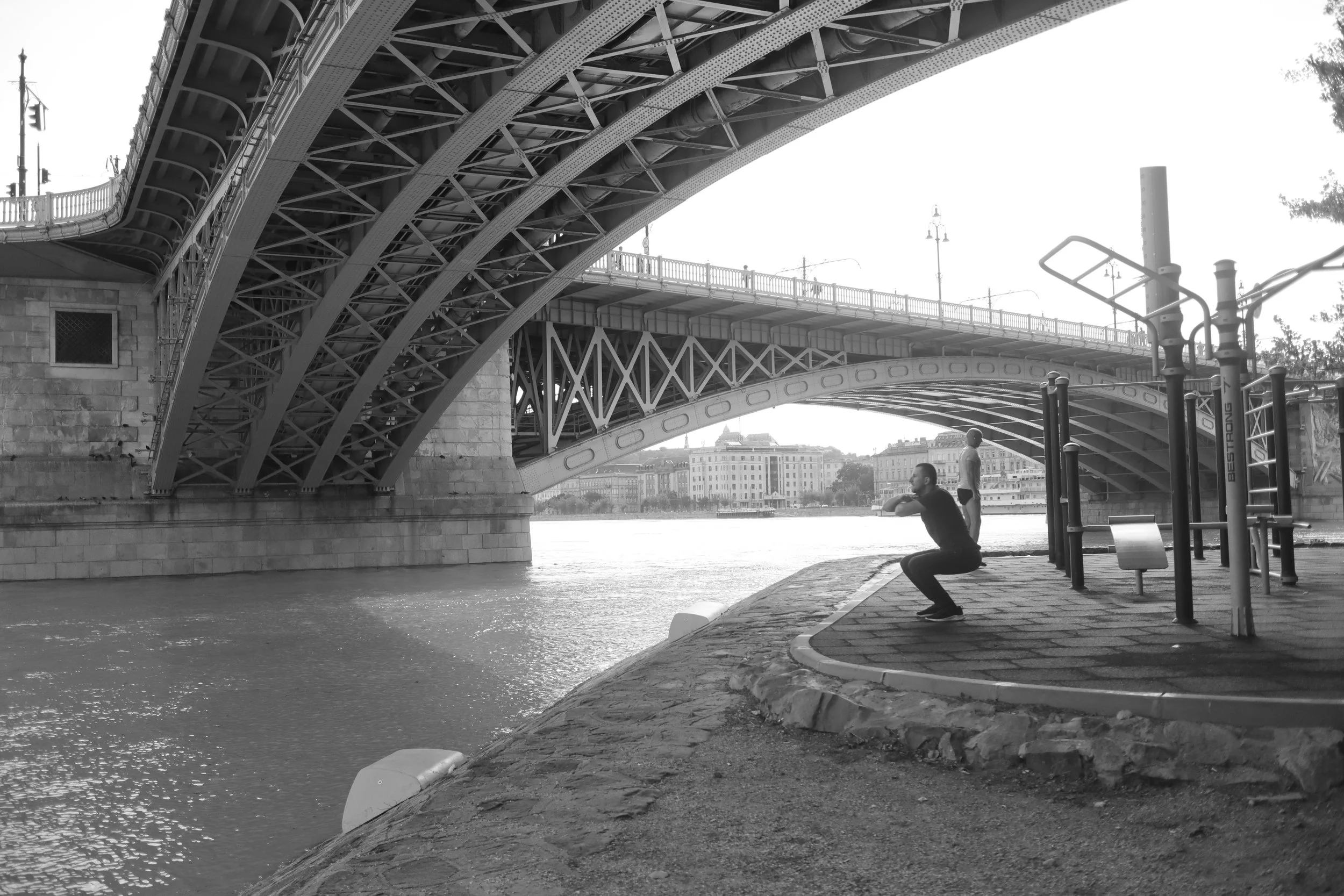

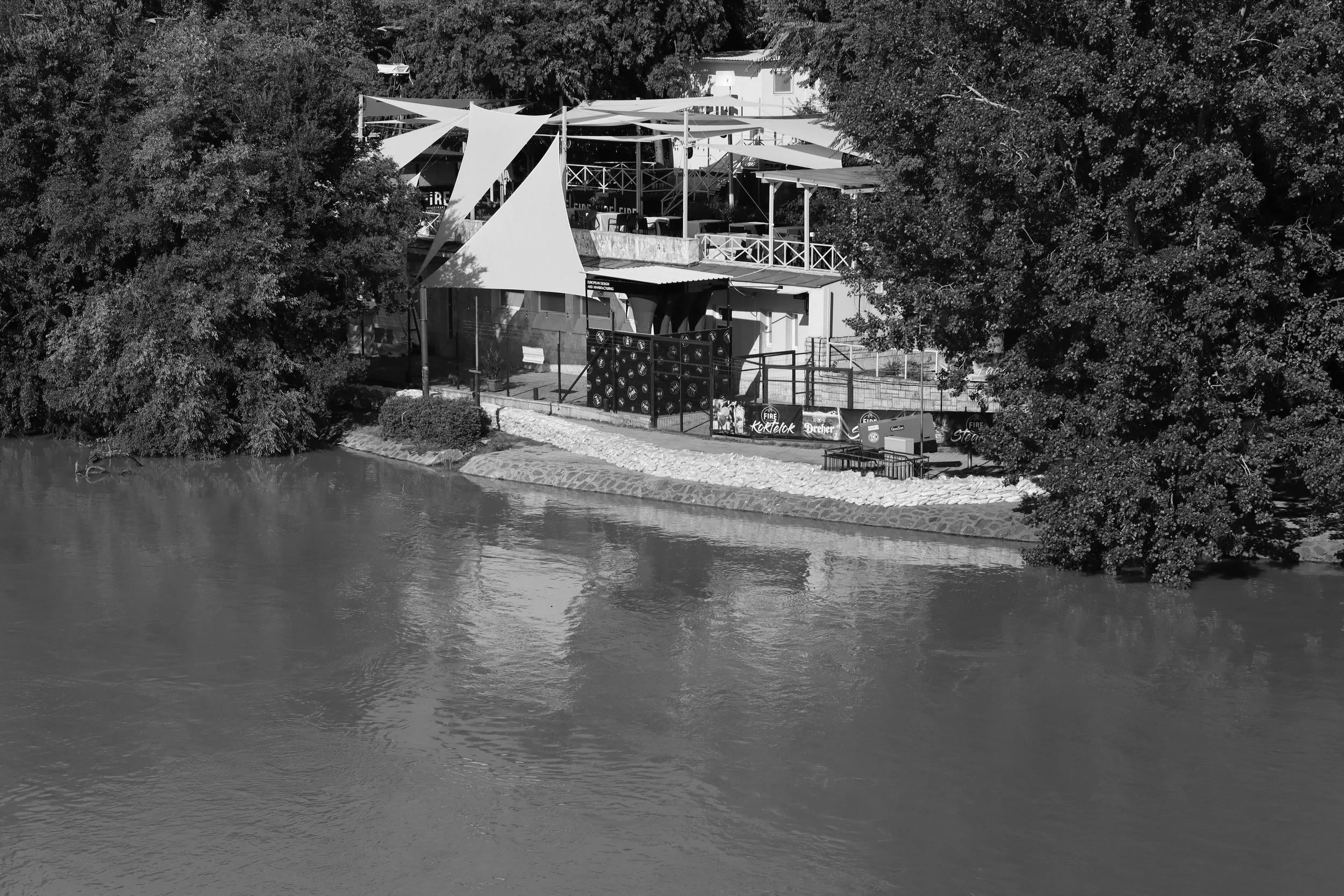

The islands of the Danube are vulnerable to flooding. Huge river-going vessels were once built by Ganz on Népsziget (Peoples Island) in the north of the city. Now the ship yard stands empty, home to the homeless and film crews looking for a dramatic backdrop. Óbuda island was also part of the riverboat industry, but now hosts the annual Sziget music festival drawing big names and huge crowds from across the continent. When the last band stops playing on arid August evenings, the drum’n’ bass start up and boom until five a.m. in the morning. The rest of the year it’s a quiet, unspoilt green oasis. This can’t be said of the more famous Margaret Island which attracts locals and tourists the year round with its excellent sites, and sounds from the musical fountain. Access was closed here as the flood waters rose this autumn and a wall of sandbags was hastily built by the army and volunteers. Only in the low-lying, southernmost point of the Island did the river break through and cut off the outdoor gym for a few days.

Disaster tourists and bystanders, myself included, wondered if the mayor’s claim that the million sandbags he supplied would keep Budapest dry. In the event they mostly did. The flooding of the low-lying embankment roads on east and west shores was inevitable. Parts of tramline two were closed in Pest as the river washed over tracks and rose against the walls of the parliament building. Prime Minister Viktor Orban kept his toes dry in the former Carmelite Monastery at Buda Castle where he does most of his business. Only a tsunami of biblical proportions could have reached him there. For a while the Metro station at Batthyány square was closed as was the suburban railway that runs parallel to the river. In neither case did the river flow into Buda’s underground transport systems. Just in a few low-lying places in Óbuda were houses and gardens flooded. Snakes, foxes and deer were seen swimming to safety from the submerged nature reserve on Háros island in the far south of the city.

All in all, Budapest was saved from the kind of disaster experienced in 1838. The defences held firm in all the key places. There was no panic. No loss of life. Just a watery but poignant reminder that Hungary is intimately connected to the rest of Europe through the Danube. The flotsam and jetsam caught up in the boat ropes and quays in the inner city hailed from foreign lands: German barrels, Slovakian trellises and Austrian gates. Once released back into the current they could continue their lonely journey to the Danube Delta and Asia Minor. I am crossing the river again without thinking of what lies beneath the bridges- that endless flow originating in the Black Forest, that lifeblood and lifetaker we so easily forget about.

Rising waters on Margaret Island Tuesday 17th September 2024

Tourists enjoy the flooded city.

Floodwaters lapping at the Parliament building

Flooded embankment road in Pest

Spinning for zander as the river rises

Outdoor gym on Margaret Island -soon to be cut off by the flood

Underground suburban railway station awaits the floodwaters

Flooded embankment road-Pest side.

Rising waters on Margaret Island- Thursday 19th September 2024

High water point on Margaret Island- Saturday 21 September, 2024.

Normal water levels at Margaret island